The video appeared on Instagram in October. A man, in the dark of night, is spray-painting over a mural in New Orleans depicting a large pair of eyes with the Palestinian flag incorporated into their pupils, paired with text reading “All Eyes on Gaza.”

“What are you doing, defacing our local art here?” the person recording the video asks.

“It’s antisemitism,” the man, Jakob Schanzer, responds. He returns to spraying black paint over the mural as the two exchange testy words.

“Jews fight back. Get used to it,” Schanzer adds. “Happy Rosh Hashanah.”

The video put Schanzer, a doctoral student at Tulane University, on a virtual hit list for the city’s vibrant street art community — even more so once the mural’s original artist, who goes by Hugo Gyrl and has Jewish heritage, touched up the piece with the phrase “Jews For Peace.”

Schanzer went to a social media acquaintance for help navigating his newfound virality, who recommended he get in touch with someone. Within an hour, he recalled to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, “I was on the phone with Ronn.”

“Ronn” was Ronn Torossian, an infamously hard-charging public relations executive who had recently devoted considerable resources to relaunching a century-old Jewish group called Betar. Like the Anti-Defamation League and many other Jewish organizations after Oct. 7, 2023, Betar wanted to fight antisemitism — but not with statements or lawsuits. Instead Torossian, a devotee of the early-20th century Revisionist Zionist thinker Ze’ev Jabotinsky who preached the power of Jewish self-defense and founded the original Betar movement in a pre-state Israel, wanted to fight fire with fire.

Soon, instead of running from the video, Schanzer was embracing it — by putting it on social media himself, this time with Betar branding. He also added his own explanation for his behavior, declaring that the phrase “All Eyes on Gaza” was, in his mind, just as bad as other pro-Palestinian rallying cries more widely believed to be antisemitic, like “Globalize the Intifada.” He added that this mural in particular was “calling for violence against Jews,” declaring, “As a strong, gay Jew, I will not cower in fear.”

It could be a mission statement for the new Betar, which, Torossian told JTA, “stands for tough, strong, proud Zionism.” The group claims to currently have “thousands” of members across more than 50 cities, and its aggressive posturing is dovetailing with an increasingly combative American Jewish right, angered by post-Oct. 7 protests and newly emboldened by President Donald Trump’s return to office. On social media Betar recruits “Bear Jews,” named after the character in the Quentin Tarantino movie “Inglourious Basterds” who beats Nazis with a baseball bat.

“Many of us believe that we are living in the days before a potential Holocaust,” Torossian told JTA. “So we think that it’s OK to stand up to antisemites, and not only is it OK, but we’re going to do it differently than the ADL. The ADL writes position papers. Hillel writes position papers. How are those position papers working out for us?”

Over the last several months, Betar has steadily built an army of pro-Israel agitators who respond to pro-Palestinian protesters with a mix of online trolling, counter-demonstrations and direct physical threats. Its archnemesis, the group’s former executive director told JTA, is the national campus group Students for Justice in Palestine. But in practice the group tends to view anyone organizing for Palestinians — or any authority figures who Betar says aren’t doing enough to stop the marching, or any Jew advocating for a more moderate stance on Israel — as a potential antisemitic threat and, therefore, target for response.

Any given day on Betar’s active social media accounts, one might find a photo of a brass-knuckle menorah; jokes mocking efforts to address Islamophobia; praise for followers who disrupted a recent New York vigil for Hind Rajab, a 5-year-old Palestinian girl killed in Gaza by Israeli troops a year ago; musings about ripping the kippah off the head of a Jew participating in a pro-Palestinian protest; a Photoshopped baseball bat directed at the mouth of Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg; and attacks on Jews from Chuck Schumer to George Soros (“Kapo of the week”) to comedian Adam Sandler. (“Shame on you, Adam Sandler,” Betar tweeted recently, falsely claiming he “hasn’t said a word about antisemitism or the Jews.”)

Now, the Trump administration is embracing policies and ideas that align with Betar. On Jan. 29 the president signed an executive order intended to counter campus antisemitism, the most eye-catching part of which suggested that foreign-born protesters who are deemed to have supported terrorist groups like Hamas could be deported.

It was a policy that, to borrow Torossian’s phrase, could have come straight from a Betar position paper. For months the group has openly gathered dossiers on what it claims are students who match that exact profile, with the stated intent of submitting them to the Trump administration for deportation.

On the street, Betar encounters have led to violence. Last spring the Shirion Collective, a pro-Israel group similar in temperament to Betar that often teams up with them, counter-demonstrated at the University of California, Los Angeles encampments alongside other pro-Israel contingents. The conflict devolved into a violent brawl with several arrests. In the run-up to the violence, Betar had declared on social media, “We demand police remove these thugs now and if not we will be forced to organize groups of Jews to do so.”

Witnesses at the time said the UCLA pro-Israel counter-protesters chanted “Second Nakba,” a reference to the Arabic word for “catastrophe” — how Palestinians refer to their mass displacement at the State of Israel’s founding. In the Forward, David Myers, a Jewish professor at UCLA and president of the New Israel Fund, called the pro-Israel contingent “a violent band of thugs intent on inflicting damage” and condemned the school for not being prepared to intervene sooner.

Recently, revisiting its statement, Betar declared, “We are proud of what we have done at UCLA. Yes if the police don’t do their job Betar will.”

Israeli professor Shai Davidai outside of Columbia University, April 22, 2024. (Luke Tress)

Betar US doesn’t just view pro-Palestinian protesters as the enemy; it also goes after other Jews, even strongly pro-Israel ones.

Columbia University professor Shai Davidai knows this firsthand. Last weekend, Davidai organized a pro-Israel counter-protest to a “teach-in” about the first intifada being planned by a coalition of pro-Palestinian Columbia groups, some of which had explicitly advocated for violence against “Zionists” in the recent past.

Together with influencer Lizzy Savetsky and the group End Jew Hatred, Davidai told JTA, the counter-protest had around 100 people turn up — including around seven Betar supporters.

Despite their tiny size, the Betar contingent immediately worried Davidai. Most of them were young men, he recalled; several covered their faces; one had a flag of the Jewish Defense League, an extremist group that the United States has designated as a terrorist organization. “All they did was scream ‘F— Gaza,’ ‘Gaza is ours,’ ‘Here’s a beeper for you,’ ‘Deport them all,’ ‘ICE, ICE, ICE,’” he said. “Just violent rhetoric.”

Davidai is no stranger to provocation: Last fall, Columbia barred him from campus after months of his vocal criticisms of the university’s handling of antisemitism. Yet he views Betar as a serious obstacle to the movement he was trying to build, not least because they were adapting the same tactics as the pro-Palestinian side: expressing support for a terror group and hiding their faces as they did so.

“I think it’s hypocritical to spend 16 months blaming all protesters who are in this Free Palestine movement for not policing their own protesters, but then let hatred and violence take root in yours,” Davidai said. “I said, ‘Look, you’re doing exactly what we’re telling them not to do….’ At some point I asked them, ‘Go do your thing, but don’t be associated with us.’ They refused.”

After the rally, Betar and its followers began targeting him online. On Instagram he blasted them for only joining counter-protests, while never showing up to rallies for Israeli hostages. The rhetoric has only escalated from there, as Betar has mobilized its followers against him, in public and private. “You will be disrupted at all future speeches,” Torossian messaged Davidai on WhatsApp, according to communications shared with JTA. “You are a radical.”

Davidai has also urged his followers against supporting any further killings or mass expulsions in Gaza, a stark contrast to Betar’s own stated views. Yet in the comments, many of Davidai’s own followers have begun taking Betar’s side, accusing him of naively trying to make peace with the enemy.

He still believes his own movement will win over Jews in the end. Betar, Davidai believes, is mainly composed of “frustrated keyboard warriors” with a misguided view of activism. “A lot of people confuse peacefulness and nonviolence with submissiveness. They confuse community organizing as weakness,” he said.

“Organizations like Betar are not interested in the free marketplace of ideas,” Davidai added. “They’re interested in canceling people they disagree with, ad-hominem attacks, shouting, counter-protesting.”

Still, he said, “They’re not as bad as people who support Hamas.”

Ronn Torossian, CEO of 5W Public Relations, peaks during the company’s 15th anniversary event at Catch Rooftop on June 14, 2017 in New York City. In 2024 Torossian relaunched the Zionist group Betar in the United States. (Eugene Gologursky/Getty Images for DuJour)

The group’s own internal operations appear as chaotic as its street actions. While JTA was reporting this story, Ross Glick was for months identified as Betar’s executive director. Glick outlined many of the group’s priorities in an extensive interview with JTA on Jan. 28, noting he had “relationships with a number of people” in the U.S. Senate and executive branch, and said several of Betar’s goals have become realized since Trump took office.

Five days later, without explanation, Betar announced Glick was no longer with the organization.

Glick stopped responding to requests for comment after his departure, while Torossian declined to elaborate beyond stating, “Ross is no longer working for Betar.” On social media, pro-Palestinian activists were circulating a 2019 New York Post article detailing Glick’s arrest on revenge-porn charges as a means of discrediting Betar.

The group has newly onboarded a spokeswoman, Sloan Rachmuth, who is a conservative activist in North Carolina who often takes video of protesters at UNC. She was arrested in November under suspicion of cyberstalking a pro-Palestinian supermarket employee before charges were later dropped.

Rachmuth, who on Tuesday called a pro-Palestinian UNC student who was stripped of a prestigious scholarship a “fat retard” on social media, said she is grateful for Betar for giving her own activism a lot of “moral support.” They are much more helpful to her cause than the Jewish federations and other mainstream groups, she said. “A lot of Jewish groups don’t do anything but talk.”

Like Rachmuth, both Glick and Torossian have faced down law enforcement over some of their Betar-related activity — and, prior to their split, seemed happiest when Betar was causing trouble.

“We are proud to have stopped numerous encampments,” Torossian said. “There will not be encampments in the United States that we do not attend.”

It’s this desire to confront that has endeared Betar to its new recruits, several of whom, like Schanzer, have gone viral for street actions countering pro-Palestinian protests. Those include a non-Jewish military veteran in Massachusetts arrested after shooting a pro-Palestinian protester who jumped him and a rabbi and his son in Milwaukee who were arrested after destroying a real-estate owner’s pro-Palestinian mural that depicted a Star of David turning into a swastika. Last week a Betar affiliate counter-protested at a demonstration outside the home of a Jewish regent of UCLA, where a pro-Palestinian group was directing threats like “Divest now, or you will pay.”

Some Betar recruits, such as Schanzer, told JTA they only became truly invested in pro-Israel causes after Oct. 7. In addition, what connects most of them is a desire to take the fight against antisemitism to the streets, and a deep antipathy toward establishment Jewish institutions that they say aren’t acting with a similar level of urgency.

Peter and Zechariah Mehler, Jewish Milwaukee residents, freely admit to having torn down a pro-Palestinian mural depicting a Star of David turning into a swastika. (Courtesy)

“My politics and Betar’s politics are very different. I’m not a right-wing guy,” Zechariah Mehler, who encountered Betar after his own Milwaukee mural incident went viral, said about his initial hesitation in joining the group.

But, he said, Torossian assured him there was a place for him in Betar, since both believed Jews should stop “just being meek and allowing ourselves to be threatened and walked over. So I said, sure.” Betar helped the Mehlers raise legal fees, and Torossian lobbied for their case in the press, calling them “heroes.” Since then, Mehler has happily promoted Betar on social media.

“I think Betar collects the people whose reaction to threats is ‘fight,’” Mehler mused, adding that such people sometimes “are a little militant.” Adapting a “Sopranos”-like, tough-guy accent, he imitated a Betar member: “I’m gonna fight this thing. No one’s gonna tell me what to f—ing do.”

Before he left the group, Glick insisted that Betar, which is a registered nonprofit, does not endorse political candidates or policy proposals in either the United States or Israel. “We’re not for or against Trump. We’re not for or against Biden or Bibi. That’s not our position,” he said. “At the end of the day, we are an educational organization promoting Zionism.”

But Torossian has represented figures in Trump and Netanyahu’s orbits, including Eric Trump and, at one point, Netanyahu’s Likud party. And since Glick’s departure, Betar’s social media has proclaimed, “We stand with @netanyahu and @RealDonaldTrump.”

Betar’s accounts frequently voice bromides closely aligned with the Jewish and Israeli far right, recently tweeting, “Both sides of the Jordan River are ours” (a quote from a song attributed to Jabotinsky) and spotlighting “friends” clad in gear from the JDL.

Asked about the JDL, Torossian, who also said he does not write Betar’s tweets, claimed he was unaware of any similarities between his group and the far-right militant gang founded by the late Rabbi Meir Kahane. He also rejects any characterization of Betar as “extreme,” “far-right” or a “militia.” Betar’s social media, meanwhile, recently shared a clip of a member expressing nostalgia for “the Rabbi Meir Kahane days.”

“We don’t want peace. We don’t want co-existence,” Betar declared after a recent chaotic hostage release from Gaza. “It’s us or them. Choose a side. Society or the rapestinians.”

Betar has also endorsed a policy proposal, floated by Trump multiple times including during a joint press conference this week with Netanyahu, to force all Palestinians in Gaza to resettle in Egypt, Jordan or other neighboring countries. The view is far to the right of nearly every large American Jewish group and the international community, which has stated for months that any permanent displacement of Gazans as a result of the war would constitute ethnic cleansing.

“I think it’s a very good idea,” Glick said about Trump’s proposal. “It’s a giant pile of rubble. How can you rebuild there?”

Betar’s messaging occasionally stretches to other right-wing talking points that have little to do directly with Judaism, like a stance against “transgenderism” and a swipe at progressive Rep. Ilhan Omar — not for her vociferous Israel criticism, but because of her efforts to help fellow Somali refugees. The group has even backed figures whose right-wing nationalist views overlap with antisemitism, like British anti-immigration advocate Tommy Robinson (who in 2023 was arrested after attending a march against antisemitism against the wishes of the march’s Jewish organizers).

This shouldn’t be surprising, Myers told JTA. The UCLA professor said he sees Betar as an outgrowth of a long culture of “toxicity” and “disinhibition” in American politics. He believes that spirit has, over the last few years, animated not just groups like Betar but also institutional Jewish groups’ way of thinking about Israel’s critics.

“It rhymes with a lot of the efforts of more mainstream organizations which, in my mind, equate support for Palestinians, Palestinian self-determination, with a pro-Hamas, pro-terrorism stance,” he said. “Betar takes rise out of that legitimization of the claim that disagreeing with Israel’s actions in Gaza is akin to antisemitism.”

For some pro-Israel activists, Betar can be complicated. “I see them post videos, and it’s like, why are you filming yourself screaming at people? That doesn’t look good,” Billie Little, a pro-Israel street artist in New Orleans who has joined forces with Schanzer, told JTA about Betar. “There are times I feel like, ‘OK, I don’t know if I want to be all-in on this.’”

Still, Little said she accepted Betar’s help in raising money for her and Schanzer to acquire paint supplies. And she’s helped Betar put up a Zionist mural in her hometown of New York City. At the same time, she notes, “I strongly disagree with them on many stances, particularly concerning their endorsement of President Trump’s plans for Gaza.”

Little said she was spurred to work with the group despite her disagreements because of its sense of urgency. Some Jewish groups — including federations like the one that commissioned her to design a mural in New Orleans — are “taking the more quiet approach, a more mild-mannered approach, a more, arguably, civil approach. Which I think is important,” she said. “But I think sometimes that approach has left many Jewish people, just laymen like us, feeling very helpless. Do I just wait for you, with this organization, to save the day? What can I do to stand up for myself?”

Jewish Federations of North America did not return requests for comment on Betar; neither did the American Jewish Committee, which often asserts itself as an antisemitism first-responder. The ADL, a frequent target of Betar’s ire, declined to comment.

On the one-year anniversary of Oct. 7, days after Schanzer’s own video, Betar pinned a post to its X profile: a screenshot of the hardline pro-Palestinian group Within Our Lifetime announcing that it had received “several violent threats from Zionists.”

Betar appended its own commentary: “#JewsFightBack.”

Ze’ev Jabotinsky (1880-1940) sits at center with soldiers of the Jewish Legion, Autumn 1918. Jabotinsky was a Russian Jewish Revisionist Zionist leader, author, poet, orator, soldier and founder of the Jewish Self-Defense Organization in Odessa. With Joseph Trumpeldor, he co-founded the Jewish Legion of the British army in World War I. Later he established several Jewish organizations in Mandatory Palestine, including Betar. (Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

In 1923, as diaspora Jews were fiercely debating what the future of Zionism would look like, Ze’ev Jabotinsky was ready to lead its right flank.

Zionist youth movements were gathering across Europe, and the Ukrainian-born writer and activist, who was intrigued by Italian fascism and sought a militaristic following that could answer to him, brought together insurgent groups in Latvia for his aims. He gave them the name Betar, after the final fortress of the ancient, failed Jewish Bar Kochba revolt against the Roman Empire.

“He organized them and gave them a common identity,” the Israeli-American writer Hillel Halkin, author of a 2014 biography of Jabotinsky, said in an interview. Key to the leader’s appeal, Halkin said, was his willingness to physically fight back.

“Jabotinsky also always believed that you never take a blow or an insult sitting down, that you have to return blow for blow, in one way or another,” Halkin said. “So for him the question would not be, is it permissible to use violence against violence? It would simply be, is it practical? Does this make political sense?”

Halkin, who lives in Israel, was surprised to learn of Betar’s resurgence in the United States. He didn’t love the idea. On the one hand, he speculated that a renewed sense of “Jewish militancy” could help “fight back against the anti-Israel militancy of the intifada, pro-Hamas people on the campuses or even elsewhere.”

Yet, he said, “I don’t think that a handful of hotheaded extremists fanning the flames are what young American Jews on campuses need.”

He also insisted Jabotinsky would probably have disapproved of Betar’s habit of swarming and intimidating pro-Palestinian protests: “I don’t think Jabotinsky would have wanted to shut anybody up who was saying the most vile things about Jews or Israel. As long as there was no incitement to physical violence.”

Jabotinsky is revered by Torossian, who grew up in what remained of an earlier iteration of the Betar movement and references the founder in Betar communications every chance he can get. The group’s website praises Jabotinsky’s “vision” and “legacy,” and reproduces the Hebrew oath he encouraged all Betar followers to take.

“Jabotinsky was, for many of us, the most formidable Zionist ever. Including Netanyahu,” Torossian said. “We believe ultimately we will only be safe in the Jewish state. If you do not make aliyah, your choice is to stand up. Jabotinsky wrote very clearly, you must fight back. Jabotinsky said very clearly, Jews must know how to fight back.”

Glick, too, grew up in Betar as a young Jew in the Cleveland area. “My first trip to Israel, when I was a teenager, was with Betar,” he recalled. “It was a nice social community.” Unlike Torossian, who was Betar’s national president for years, he drifted away from the organization as he became an adult.

The two men had vaguely known each other through New York marketing industry circles before connecting at a counter-protest in Grand Central Terminal last summer. Glick recalled getting into a “screaming match” with a protester, saying, “I would never shy away from somebody who gets in my face.”

Torossian, meanwhile, had recently been arrested at Syracuse University, where a child of his is enrolled, for getting into a fight with an encampment protester. He was charged with disorderly conduct and trespassing. (When he described the incident to JTA he noted that the man he’d fought had previously been convicted of manslaughter and that, in his view, the school had been negligent in not having his adversary removed from campus earlier.) The episode had convinced him that the Jews needed to heed the example of Jabotinsky again. Torossian told Glick he was looking to relaunch Betar for the age of Oct. 7 and social media.

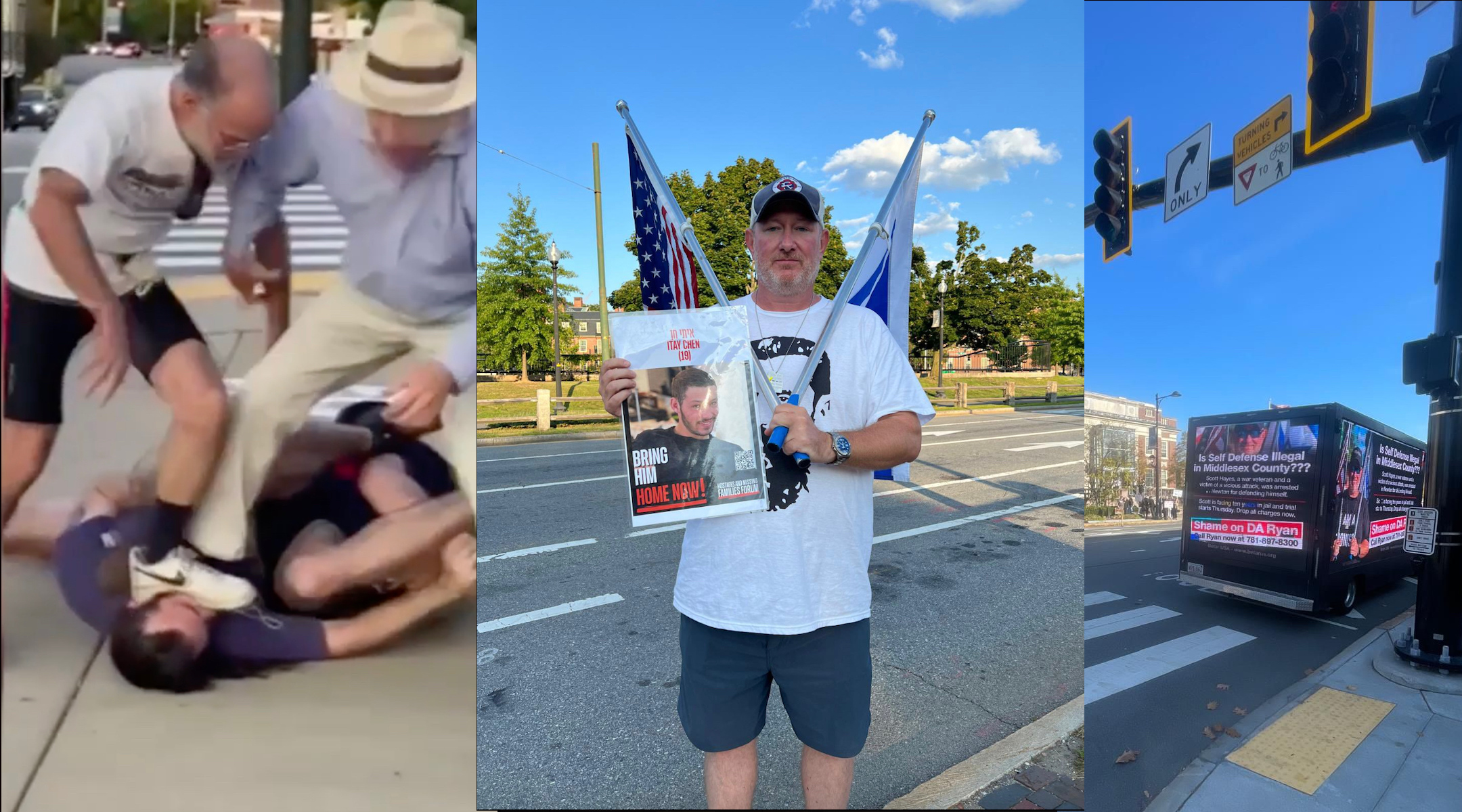

(L-r) A scene from the September 2024 brawl between non-Jewish pro-Israel activist Scott Hayes and a pro-Palestinian protester that led to Hayes’s arrest and, later, the protester’s; Hayes at a protest carrying American and Israeli flags and holding a hostage poster; a truck Betar sent to Massachusetts with a message in defense of Hayes. (Screenshots via X and courtesy of Betar US)

Glick agreed to become the group’s new director, and the two immediately set out trying to grow their national presence. After Scott Hayes, a non-Jewish Iraq War veteran in Newton, Massachusetts, was arrested and charged with assault and battery for shooting a pro-Palestinian protester who attacked him, Betar hired trucks to drive through town reading, “Is self defense illegal in Middlesex County??”

Video from the protest shows an activist sprinting at Hayes from across the street to tackle him; Hayes, who was armed, told JTA he had fired his weapon in self defense and later administered first aid to his assailant. His case, which is ongoing, has become a local flashpoint not only for Israel-related criminal cases, but also for Massachusetts self-defense laws.

Torossian reached out to Hayes after the case was publicized and “offered help,” Hayes said. “He’s able to make things happen. He’s been extremely supportive.”

“I think Betar has a place in the world,” Hayes said. Currently enrolled in an online Intro to Judaism class, he offered an analogy: “I would view them as modern-day Maccabees.”

In addition to helping some of their members navigate the law, Betar is also involving itself in other legal matters. The group is advocating for the family of Aviv Broek, a 21-year-old Israeli locksmith who was murdered in Memphis in November. Authorities have said the ongoing investigation has uncovered no evidence the murder was motivated by antisemitism. But Torossian is convinced otherwise, and Betar recently disseminated a statement on behalf of a Broek family friend calling for a hate crimes investigation.

“Today in 2024, we are Israelis and we are aware of the reality that Jews are being hunted worldwide. The enemies of the Jewish people have called to globalize the intifada and we are concerned that this may be the case in Memphis,” the friend wrote on Betar’s website, next to a large illustration of Jabotinsky. Betar also says it will help the Broek family with the case and advocate in Washington on their behalf.

The group’s campus activities have prompted the attention of the universities, as was the case for a provocation Betar stirred up in November at the University of Pittsburgh.

At the campus, where Glick’s son is enrolled, Betar posted on social media that he would be handing out “beepers” to the campus SJP chapter. It was, he now says, a bit of dark humor related to Israel’s “exploding pagers” operation targeting Hezbollah militants in Lebanon last September. But the university didn’t think it was so funny, and soon alerted its student body to what it said were threatening texts being directed at Palestinian students. The university did not respond to a JTA request for comment about the incident.

Glick finds the whole affair absurd, insisting that SJP is the group that should really be investigated. He did find a high-profile defender in Pennsylvania Sen. John Fetterman, an especially vocal pro-Israel Democrat; the two met up on Capitol Hill, where, on video, Fetterman told Glick he approved of the pager joke.

“The beepers thing, I love it. I love that s—,” the senator told Glick during their hallway encounter, which was condemned by the Council on American-Islamic Relations.

Even after breaking up with Glick, Betar has fully embraced the beeper trick, recently dropping one into the pocket of prominent Jewish pro-Palestinian academic Norman Finkelstein. After Peter Beinart, a Jewish journalist and academic who argues against Israel as a Jewish state, recently published a New York Times opinion essay titled “States Don’t Have a Right to Exist. People Do,” Betar wrote on X, “We urge all Jews on the upper west side to give Peter Beinart a [beeper emoji].” Beinart told Haaretz he considered the Betar tweet to be a violent threat “like a magnitude beyond anything I’ve experienced before.”

Betar has a clear narrative when it comes to incidents like these: It’s never at fault. Any acts of violence are only self-defense; any accusations of promoting extremism are a vicious antisemitic smear; and any persecution of Jewish counter-protesters is laughable next to the vast number of protesters on the other side who, Betar contends, pose a much greater threat yet are allowed to roam the streets freely.

Betar is hiring for more full-time positions, and touts an endorsement from the singer Matisyahu, who has since Oct. 7 become an aggressive defender of Israel and seen venues cancel his concerts. “We’re trying to operationalize,” Glick said prior to his exit, expressing a hope to develop “positive relationships with universities” so they can bring Zionist speakers to campuses.

Then, contrary to many of his group’s actions, he extended an invitation to the pro-Palestinian perspective: “If the opposing side wants to check and counter, no problem. Let’s do it in the open. Let’s have a debate. Let’s record it. Let’s share with all the students.”

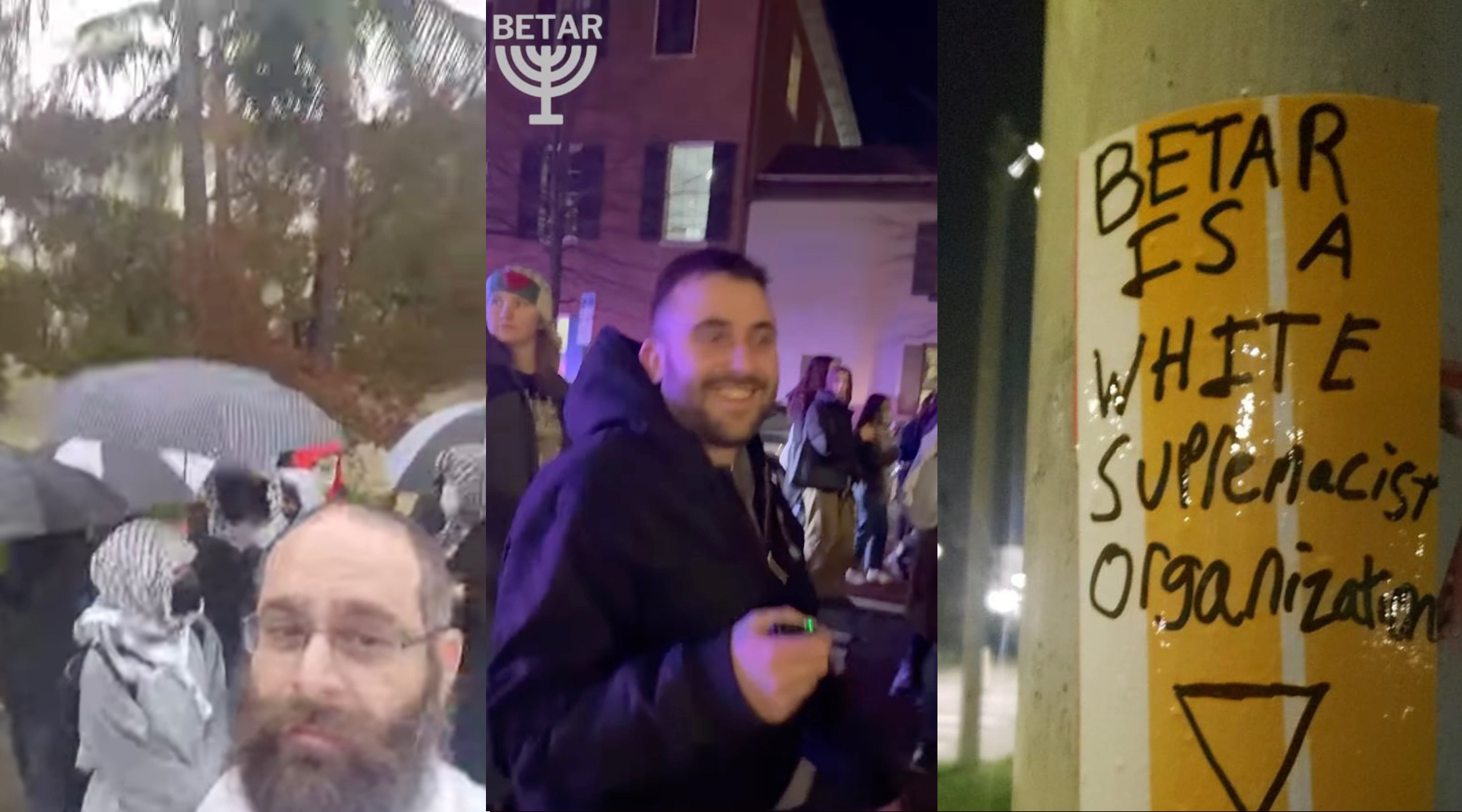

(L-r) A Betar supporter films pro-Palestinian protesters who targeted the home of a UCLA regent in Los Angeles; a Betar member mocks pro-Palestinian protesters in New York; a sign attacking Betar and including the inverted-triangle symbol of Hamas in New Orleans. (Screenshots via Instagram)

Jabotinsky never got to set foot in the state of Israel he advocated so fiercely for. He died of a heart attack in 1940 while visiting a Betar camp in New York, at the age of 59, eight years before Israeli statehood.

At the time of his death, Halkin said, the movement he championed was getting away from him — particularly as Betar members stoked rising tensions between Arabs and Jews in Mandate Palestine in the 1930s, something Jabotinsky, who advocated for a degree of Arab-Jewish coexistence, ardently opposed. “If someone had to go and put a bomb in an Arab marketplace and set it off, it was generally Betar that did this,” Halkin said.

Betar’s influence waned after the founding of the State of Israel, as most Israelis embraced a more left-leaning kibbutznik form of Zionism and their fascist-leaning approach fell out of fashion. Chapters across the Diaspora remained active, and some influential Israelis, including former Prime Minister Menachem Begin, the late Israeli statesman and diplomat Moshe Arens and the scholar Benzion Netanyahu, the current prime minister’s father, have traced their political evolutions to the movement. Beitar Jerusalem, the professional soccer team infamous for its racist hardcore fans, also takes its name from the movement.

Betar US hopes that tomorrow’s Jewish leaders will also come out of the movement. Before he left, Glick said he hoped to soon “activate in a more formal way,” with official leadership positions, chapters and campus clubs.

“I’d be very concerned by what Betar US has planned,” Myers said, calling the group’s beeper drops “very scary.” Recently Netanyahu offered his own version of a beeper joke, giving Trump a “golden pager” during his recent state visit.

“It seems we’re half a step away from physical violence,” Myers said. “And I would say, if there are respectable parties left in the Jewish community, this is a moment of reckoning, to say, ‘Wait a minute, this is going way too far.’”

Glick said he knew that Betar is not where the Jewish mainstream is. But like the Betaris of old, he sees them as doing the dirty work the rest of the Jewish people is too scared to do.

“When I go to synagogue, I can’t tell you how many Jews give me a hug, give me a handshake, give me a pat on the back,” Glick said. “Out of one side of their mouth, they’re like, ‘Oh my God, you’re meshugenah. This is too aggressive. It makes us look bad.’

“And on the other side of their mouth, they’re like” — and here his voice dropped to a whisper as he imitated his scared fellow congregants — “‘Thank you very much. We need you.’”

Keep Jewish Stories in Focus.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·