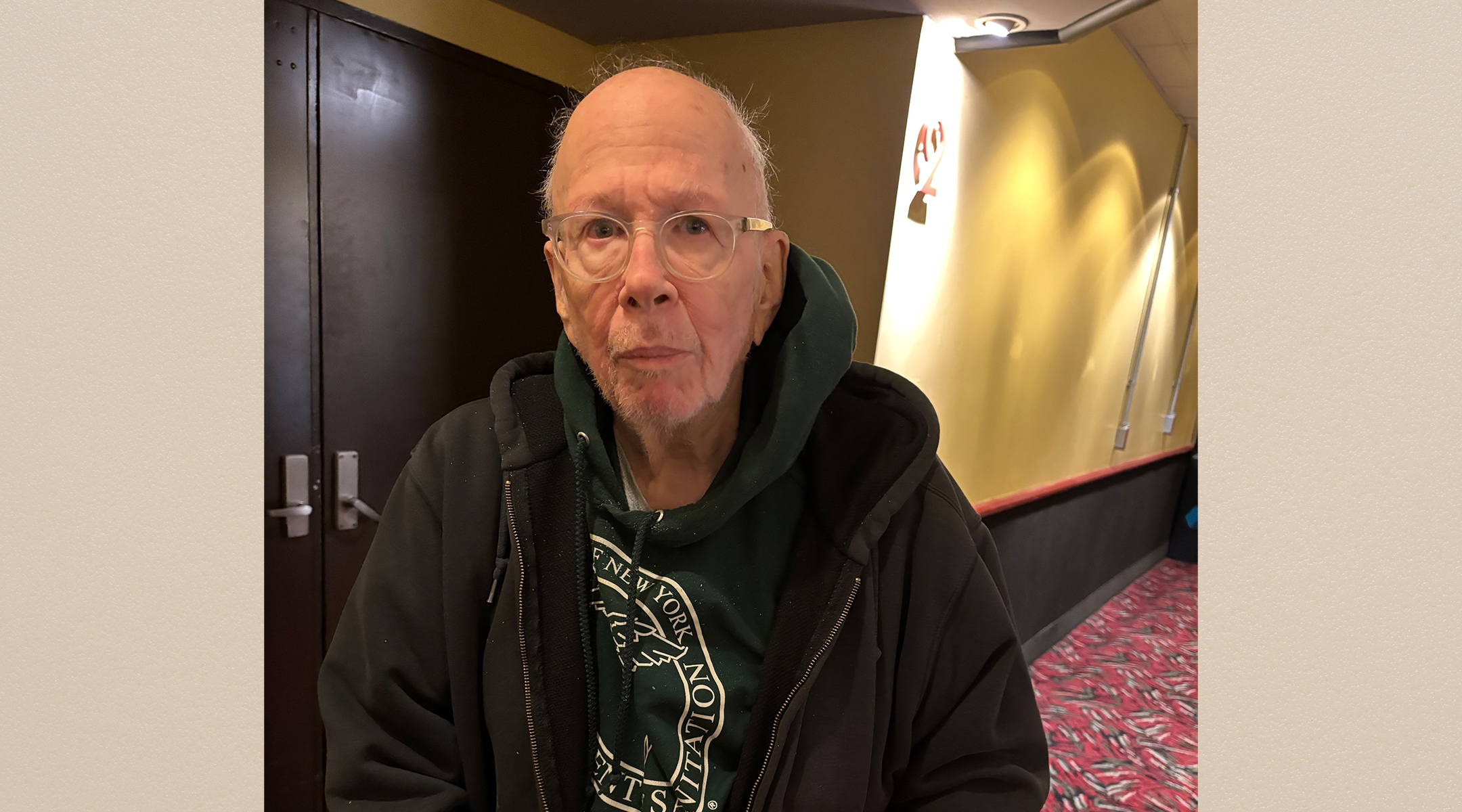

A.J. Weberman — the writer and gadfly who gained notoriety in the 1970s by picking through Bob Dylan’s garbage — recently watched “A Complete Unknown,” the new biopic about the Jewish singer-songwriter.

He didn’t like it.

Even before the movie was over, Weberman, a lifelong Dylan obsessive who coined the term “Dylanology,” made his opinions known. Throughout the 141-minute film, Weberman made several vocal efforts to set the record straight, yelling out “Bullshit!” or “That never happened!” — prompting some gray-haired Baby Boomers in the nearly empty theater Sunday afternoon to shush him.

Nonetheless, this reporter was eager to hear Weberman’s review once the credits rolled. Characteristically, Weberman did not mince his words.

“It sucked,” he declared afterwards in the lobby of the AMC Orpheum 7 multiplex on East 86th Street. “It’s got nothing to do with reality.”

Weberman is intimately familiar with Dylan’s reality. The inventor of the word “garbology,” or “searching through trash for journalistic clues,” according to the New York Times, Weberman, 79, has spent a lifetime making himself something of an expert on the Jewish icon, who was born Robert Zimmerman in Duluth, Minnesota, in 1941.

While the Dylan biopic is introducing his myth and mystique to a younger generation, aging obsessives like Weberman are fiercely protective of the Baby Boomer icon who is also the only musician to win a Nobel Prize for Literature. In many ways, Weberman, who’s been called “the king of all Bob Dylan nuts,” also represents a specific strain of Jewish fascination with Dylan, whose work and life are dissected by fans with almost Talmudic devotion.

“I thought there was a lot of left-wing thought embedded in his poetry and it was my job to translate it,” Weberman said of the roots of his fascination with Dylan. “He was the first one to be a serious poet and put it to rock music. He was singing poetry.”

Jewish actor Timothée Chalamet portrays Bob Dylan in the new biopic “A Complete Unknown.” (Macall Polay, Courtesy of Searchlight Pictures)

And yet, Weberman didn’t run to catch the film on opening day; “I was waiting for the bootleg version,” he quipped. Despite his poor review, Weberman’s opinion of “A Complete Unknown” wasn’t all sour grapes. He described the performance by Jewish actor Timothée Chalamet — who portrays Dylan and sings his songs in the film — as “very good.”

In fact, Weberman begrudgingly admitted he was rooting for Chalamet, a 28-year-old Manhattan native whose grandfather was an important Jewish writer from the Bronx, to clinch an Oscar for the role. “Somehow my fate is intertwined with Bob, and I like to see him succeed,” Weberman said.

Such grandiose statements are typical from Alan Jules Weberman, who lives in the Riverdale section of the Bronx with his wife, Nonet, a retired teacher. Case in point: Weberman claims he was instrumental in Dylan winning that Nobel Prize. This theory involves a mid-1960s psychedelics-infused listening session with Gordon Ball, who went on to become a college literature professor and pressed for Dylan to be awarded the Nobel every year.

“I turned the guy on to Dylan!” Weberman insisted.

(Ball remembers it differently: “I loved Dylan’s work before I met Weberman,” said Ball, who described the discourse the Dylanologist imparted over the years as “wholly uninteresting. It was not helpful.”)

“A Complete Unknown,” which opened on Dec. 25, chronicles Dylan’s first four years in New York, beginning with his arrival in 1961. It concludes in 1965 when Dylan caused a major scandal at the Newport Folk Festival by “going electric.” (During these years, Weberman attended Michigan State University, travelled in Mexico and returned to New York to finish college.)

Weberman didn’t cross paths with Dylan himself until at least five years after this seismic event. By then, Weberman had already become a Dylan expert: In 1969, he published a 25-page pamphlet, “Dylanology,” launching a movement of fellow Dylan fanatics.

In 1973, he completed an alphabetical list of the important words used in Dylan’s songs, which entailed typing all the lyrics on punch cards using a mainframe computer at NYU (a friend who was an alumnus leant Weberman his ID). Today, the magnetic tapes reside at Cornell University’s Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, whose Bob Dylan and A.J. Weberman collection includes an Esquire magazine article by Weberman, “The Art of Garbage Analysis.”

According to Weberman, the first time he met Dylan in the flesh was in 1970. He also said he used to drop by the art studio on Houston Street that Dylan used for painting and composing songs on a regular basis, spending several hours at a time with him.

“I hung out with him all the time in his studio on Houston Street,” Weberman claimed. “I spent more time with him than any other music journalist.”

But during the heady days of the counterculture, when many saw Dylan as a prophet of profound societal transformations, Weberman concluded that Dylan was apolitical and neglecting ”the movement” — a judgment that divided other Dylan acolytes.

No longer on intimate terms with the singer, Weberman at one point began sifting through the trash at Dylan’s home on MacDougal Street in the West Village. He got the address from Izzy Young, who produced Dylan’s first New York concerts and whose Folklore Center in Greenwich Village served as a folk scene of the 1960s.

“Considering that I couldn’t get inside [Dylan’s house], I wondered: Is there something that was inside that’s outside now?. That’s his garbage,” Weberman explained. Among the items Weberman recovered from Dylan’s trash were a draft of a letter to Johnny Cash in Dylan’s handwriting, a suggested track list for a forthcoming album, a letter Dylan had written to his mother and a photo of Jimi Hendrix.

Of course, Dylan did not approve of Weberman’s pursuits; he became furious after his first wife, Sara, confronted him.

On another occasion, Weberman brought about 40 students from his Dylan class at Alternate University, an unaccredited counterculture educational institution, to the singer’s townhouse. Dylan learned that Weberman was organizing a block party for his 30th birthday and warned Weberman not to proceed with the plan. Weberman proceeded; the Dylanologist said “thousands and thousands” of people showed up on May 24, 1971, causing the NYPD to shut down MacDougal Street. A story in the New York Daily News had a smaller crowd estimate. “Dylan Misses Big-30 Bash,” the headline said, noting that the singer was in Israel and that hundreds partied in his absence.

In the aftermath of these events, Dylan made a series of angry phone calls to Weberman, who recorded them, apparently without the singer’s knowledge. The recordings were released several years later as an LP on Folkways Records titled “Bob Dylan vs. A.J. Weberman: The Historic Confrontation,” though it was taken off the market just a few days after its release.

According to legend, Dylan was riding his bicycle in the East Village when he unexpectedly ran into Weberman. The gloves came off.

A.J. Weberman in the theater after seeing “A Complete Unknown” in New York on Jan. 5, 2025. (Jon Kalish)

“Dylan got off the bike and didn’t say a word. He just started pummeling A.J.,” recalled Brooklyn writer Mark Jacobson, who chronicled Weberman’s hijinks for the Village Voice and Rolling Stone.

Jacobson broke into laughter as he recounted what Weberman told him about the encounter. Weberman said that while the singer was assaulting him, “All I could think about was how great it was getting beat up by Bob Dylan.”

“A.J.’s been living off that for a long time,” Jacobson said.

Weberman’s obsession with the singer — combined with his propensity to make outrageous claims — has led to some hostile media coverage over the years. The New Yorker called him a “creep.” Rolling Stone described him as Dylanology’s “most reviled figure.” And Tablet prefaced a 2015 interview with him by saying, “Alan Weberman is a stone cold meshugganeh.”

Larry Yudelson, a veteran Jewish journalist who started a website in 1995 about Dylan’s connection to Judaism, said Weberman’s deeds and words speak for themselves.

“Weberman very much validated Dylan’s decision to not be the Prophet and Oracle that he was, briefly, and many wanted him to continue to be,” Yudelson, the publisher of Ben Yehuda Press, wrote in an email.

Weberman seems impervious to these harsh assessments. “If they really thought I was crazy they wouldn’t waste their time writing about me,” he said. “The way I choose to live my life is far from normal for most people and I understand that. I am way ahead of my time.”

Nonetheless, the only thing Weberman has done longer than obsess over Bob Dylan is deal marijuana, a trade he engaged in well into the 21st century. He claims “the Feds” seized $1.2 million he had deposited in a Luxembourg bank.

“You think a nut could have amassed that kind of money dealing only in ounces?” Weberman wrote in an email.

(In fact, in early 2022, when YIVO curator Eddy Portnoy visited Weberman’s home to pick up a cartoon for an upcoming exhibit on Jews and cannabis, “Am Yisrael High,” Portnoy said that Weberman tried to sell him some weed, and that he showed up at the opening of the exhibit giving out joints of “glatt pot.”)

Weberman grew up in Brooklyn; his father was a very observant Jew, his mother less so. Weberman said his proclivity runs in the family: his father went through the household garbage to make sure his wife wasn’t buying non-kosher food — though that may be just one more bit of fabricated personal mythology. Among Weberman’s many fantastical claims is that Dylan wrote “Like a Rolling Stone” for Barry Goldwater’s presidential campaign in 1964, that Paul Simon wrote the song “You Can Call Me Al” about him and that he, Weberman, exposed the conspiracy behind the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. (The CIA did it, he claims.)

Weberman was also involved in the Jewish Defense Organization, one of two offshoots of the militant far-right Jewish Defense League, which has been designated a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center. The JDO’s website — along with Weberman’s personal site — was seized as a result of a slander judgement against Weberman and JDO founder Mordechai Levy in 2002.

These days, Weberman is working on a website that promotes conspiracy claims surrounding the death of President Biden’s first wife and the attempted assassination of Donald Trump.

He’s also finishing another Dylan book: “The Immortal Spirit of Bob Dylan” runs more than 340 pages at this point. In it he confesses to producing and selling a bootleg edition of Dylan’s poetry and prose collection “Tarantula.”

“I’ve been studying Bob’s poetry for over 50 years,” he writes in the book, “and I still don’t understand some poems and I probably never will.”

Asked if he has hopes of getting the book published, Weberman replied, “Slim hopes.”

Jewish stories matter, and so does your support.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·