Who is Jonathan Rauch, a gay Jewish atheist, to write a book about how conservative American Christians are failing themselves and democracy?

“With that background, it’s certainly the most presumptuous thing I’ve ever done,” Rauch, the author of “Cross Purposes: Christianity’s Broken Bargain with Democracy,” told me. “I come to this in the spirit of both humility and chutzpah.”

Rauch’s new book takes Protestants to task for a “politicized, partisan, confrontational, and divisive” version of faith that has helped make America “ungovernable.”

By abandoning the humility and forgiveness embodied by Jesus, writes Rauch, evangelicals especially have embraced a “Church of Fear” that is not only toxic to the body politic, but antithetical to Christianity. The problem is not just Christian nationalists who represent a militant belief in Christianizing the government, but everyday Christians who are sympathetic to the idea that their churches should focus on “winning in politics and winning in the culture wars.”

He points to evangelicals’ embrace of the decidedly “un-Christian” Donald Trump, their partisan stances on climate change, immigration and divisive cultural issues, and their own sense of persecution and grievance — represented this month when Trump announced plans for a new federal task force to fight “anti-Christian bias” — as obstacles to the kind of civility and compromise that the founding fathers (nearly all white Protestants) depended on to uphold the Constitution.

“Our secular democracy does not function well when Christianity is a meltdown and driving people away from the values that the founders counted on,” said Rauch, 64, a senior fellow at The Brookings Institution and author of eight books on public policy, culture and government.

“Cross Purposes” is also in part a rebuttal to an article Rauch himself wrote for The Atlantic in 2003, when he argued that religion “remains the most divisive and volatile of social forces.” In the decades since, and in talking with pastors and reading the literature on Christianity and the public sphere, he’s come to appreciate what religious values can contribute to the body politic. To that end he is critical of fellow liberals for denigrating religion, themselves rejecting compromise and ignoring the public’s need for “spirituality, transcendence, and morality anchored in more than the self.”

“Faith and secularism need each other to function,” said Rauch. “I think it’s necessary to address secular people like me and say, ‘Guys, we blew it. This Christianity is a load-bearing wall in our democracy, and to the extent that we help dismantle it, we’ve got to stop.’”

As for the Jewish stake in all this? “We’re a small minority religion. In case you hadn’t noticed, we have our own problems right now,” said Rauch, who interviews pastors and scholars who are seeking to create a kinder, gentler, less-politicized church. “But we can give a sympathåetic ear to our Christian friends, and I know rabbis who are doing that in some pretty wonderful ways.”

Rauch spoke to me via Zoom on Tuesday from his home in Northern Virginia. Our conversation was edited for length and clarity.

At the second of two National Prayer Breakfasts earlier this month, President Trump announced his plans for a new federal task force to fight “anti-Christian bias.” You and other critics say there is no such thing, that Christians and other religious groups have been on a decade-long winning streak at the Supreme Court, and that according to Pew, in 2023 only 27 percent of Americans took an unfavorable view of evangelicals. Where’s the sense of persecution coming from?

It’s a bunch of things. The first is demographic change. The country is no longer the white Christian America that a lot of them grew up in and never will be again. A second is pressure from the secular world, and that’s everything from cell phones and pornography to transgender ideology and everything in between. The third factor is demagoguery from Trump and Republicans and Fox News, who stir up fear very deliberately.

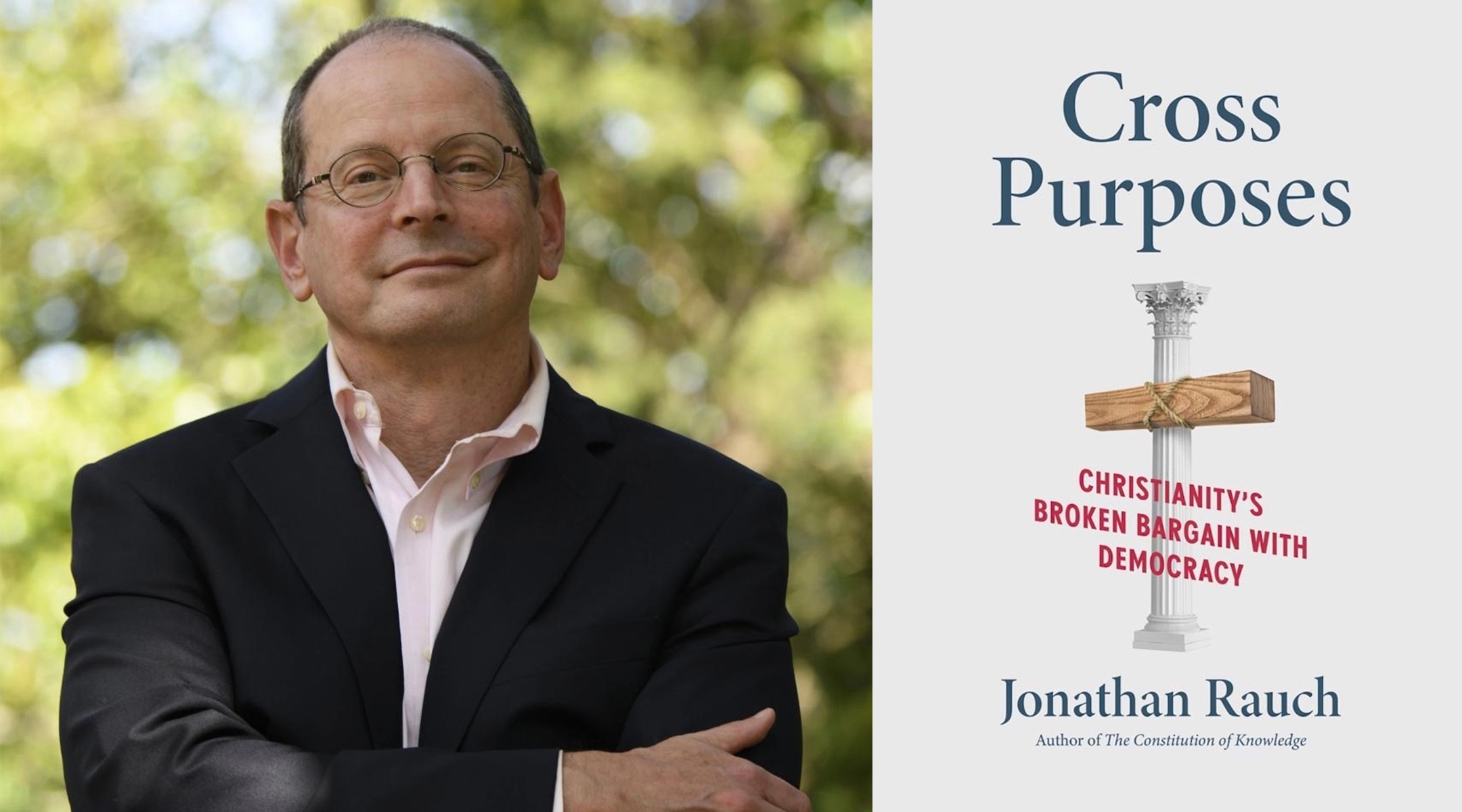

In his book “Cross Purposes,” journalist Jonathan Rauch — a Jewish atheist — explores the shortcomings of secularism and the “disastrous choices” made in response by conservative Christians. (Yale University Press)

The other thing they’re afraid of is that they’re shrinking. Their numbers are just declining catastrophically as people switch from being Christians to “nones.” A lot of it has to do with decline in status relative to other groups, and some of it is just, frankly, political. “It used to be our country; it isn’t anymore. We used to win, now we lose.” That’s, of course, not true. Obviously, they’ve won in a very big way.

This sense of persecution by evangelicals and Christian nationalists goes hand in hand with what you describe as the “Church of Fear.” How do you define that and what is its alternative?

The Church of Fear is a church that emphasizes exactly what we’re talking about, which is the notion that Christianity is in danger, your country is in danger, and if we don’t win the next election, it will be the end of life as we know it. It’s a sense of maximum panic and fear focused on this world and not on the next world. I’m not a Christian, but Christians say they’re supposed to be afraid, but of God, not of their fellow citizens, and of being judged in the next world, not of being judged or losing politically in this one.

But a fearful Christian might say, “you — as in secularists and liberals — forced us into this position of fear and fighting back.” You mentioned pornography and gender ideology, and in your book you cite (disapprovingly, I know) the so-called post-liberals who blame “an aggressively godless, consumerist, hyper-individualistic, and self-absorbed culture which dissolves faith and tradition.” Perhaps Christians are right to be fearful?

I accept it up to a point. It’s hard to be a person of faith in a secular, consumeristic, individualistic society, and that’s always been true, but I don’t accept it past that point. And the point where I don’t accept it is when Christians make catastrophic choices that betray their own faith and the principles that underlie that faith. And as a result of making those catastrophic choices, people begin to flee from their religion, from Christianity, because they perceive it’s no longer on the level, and that seems to be what’s happening.

Nothing about secular culture forced them to embrace the likes of Donald Trump and his MAGA movement, which are profoundly anti-Christian in their behavior and their teachings.

What makes MAGA anti-Christian?

Well, where to begin here? Here I rely on Christians. When Christians explain the core of their faith, they say that there are three elements that stand out, three pillars. Number one, don’t be afraid. Number two, imitate Jesus. And number three, forgive each other.

First, MAGA is about maximum fear. “They’re coming to get you. You must fight back, because you are in danger. Your faith is in danger, your country is in danger. You are being invaded by immigrants, secular people are turning your children into transsexuals,” and so forth and so on. Fear is the specialty of the MAGA movement.

Number two, imitate Jesus. Jesus taught the equal dignity of every person. He taught civility. He taught fundamental equality. He taught never using people as means to an end, but always as ends in themselves, especially the marginalized and the poor. You see the opposite of those behaviors in MAGA, which is all about chest-thumping power and often ridiculing the weak and the marginalized. Jesus was not interested in power. But that is precisely the deal that Donald Trump has offered evangelicals: You give me loyalty, I will give you power. And they’ve taken that deal.

And then finally, forgive each other. Judgment belongs to God, not to humans. Our job in this world is to get along as best we can and forgive each other and be kind. And of course, the sentiment “I am your retribution” is very much the opposite of that.

At the core of your book is your contention that the politicization of Christianity isn’t just bad for Christians and betrays their own values, but it has turned out to be “a crisis for democracy.” How so?

I’m not a Christian. It’s not my mission in life to save Christianity. I am a gay, liberal, small-d democrat, and I fear that the country is becoming ungovernable, and I believe Christianity’s collapse has been a major factor in that. The founders told us again and again that they were giving us a system of government which did not stand entirely by itself. It needed support from what they called republican virtues, which are things like lawfulness and truthfulness and civility and being civically educated and being tolerant.

And those values map very well onto the values of Jesus that we’ve been discussing. You know, “don’t be fearful” translates into “it’s not the end of the world if you don’t win the next election. So don’t cheat or pretend you did.” “Imitate Jesus“ translates into “treat other people with civility and decency, especially the weak and the marginalized,” and “forgive each other” translates into, “if you win an election, don’t crush the other side, treat them with the same decency that you will expect they’re in charge.”

So the collapse of Christianity, both in numbers and in its turning sharp and partisan in the Evangelical world, has left those values unspoken for all too much. So we get this big gap in American life. People are looking for meaning in partisan politics, where they’re not going to find it, and they’re bringing into partisan politics religious zeal, which politics can’t support. All of that is making us ungovernable.

But a secular critique might say, well, good riddance to religion, to obscurantism, to supernaturalism. Can’t we find those same virtues in a secular, classically liberal society that embraces them without the baggage that comes with believing in one’s God above everyone else’s, without scripture that treats homosexuality as an abomination and women as subordinate to men, and without churches that have frankly an abysmal track record when it comes to race? Why can’t we develop this among the “nones”?

Well, that’s exactly what I thought 22 or 23 years ago: Isn’t it great that we’re secularizing and we no longer need the crutch of religion, which is divisive and dogmatic. Well, the job of a journalist is to look at the world and understand what’s happening. And I was wrong as an empirical matter. A lot of things have happened since 2003 [when Rauch wrote his article in The Atlantic], but one of the things that’s happened is the unprecedented collapse of Christianity and its replacement with the secular pseudo-religions and hyper partisanship and all the negative indicators on things like belonging, friendship, social isolation, loneliness, depression, anxiety and community. We’ve tried the experiment of secularizing at an unprecedented pace, and it’s not working out very well.

People are looking for meaning in life. They’re looking for answers to the big questions: Why am I here? Where’s the difference between right and wrong? What’s my purpose? And the failure of Christianity has not led to some kind of benign enlightenment liberalism; it’s led to a lot of, as it were, false gods, like MAGA and wokeness, which are actively toxic, and SoulCycle and crystals, which are actively useless.

At this point I think a lot of my readers might be wondering, okay, give me an example of a church that represents the values the founders were counting on. And having read the book I know you are going to point to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, whose followers voted for Trump in far fewer numbers than other conservative Christian groups. Why the Mormons?

They’re on the level. They’re not just talking the talk — they’re walking the walk. The clearest demonstration of that was their active support for the Respect for Marriage Act in 2022. Their church is against homosexuality and regards it as a sin, and is against same sex marriage. It’s very conservative, and in the U.S. is very white, so it looks a lot demographically like white Evangelical Protestants. Yet instead of hunkering down and joining the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops and most Evangelicals in fiercely opposing the Respect for Marriage Act, they supported it and helped adopt a bill that enshrines my marriage to a man in federal statute, along with some very important landmark protections for religious liberty and thus space for their church to dissent.

You make a distinction between “thin” Christianity and “thick” Christianity. Thin religion asks too little of its adherents to provide meaning and morals distinct from secular culture, and “thick” religion is what you call “both demanding and enfolding, combining high personal investment with high communal returns.” You write that you attended Hebrew school and Jewish sleepaway camp growing up. How did that inform your thinking about religion?

This is a topic for a whole ‘nother conversation, but if you ever saw the Coen Brothers’ movie “A Serious Man,” that’s my upbringing, in a nutshell, except transfer it from Minnesota to Phoenix, Arizona. My Conservative Jewish upbringing was pretty thin actually. When I was a kid, you got a bar mitzvah and would never be seen [in synagogue] again. You didn’t really know what the prayers meant. You just said them. There was a sense of routinization about it, and that alienated me.

The “Stop the Steal” campaign to overturn the results of the 2020 election, one of whose symbols became the upside-down American flag, found many supporters among conservative Christian groups. (Screenshot from “God and Country”)

In your book you write something else about Judaism, or at least referencing Judaism. You talk about the “exilic mindset,” which I know Jews are familiar with, and which you describe as “a sense of being outsiders looking in.” Why do you think Christians, so long used to being in the majority in this country, need to think like they’re in exile?

It’s building on the work of Christian thinkers, especially the former president of Fuller Theological Seminary, Mark Labberton. He uses that term to mean that Christianity is its truest self when it stands outside of politics and mainstream culture and says, “How can we bring the word of the gospel to this society?” Jesus himself was in exile. His family were refugees, and that’s still in the DNA of Christianity. So the exilic mindset is one that does not take for granted that “we should be running the country. We should be the political winners in this society.” It’s very much the opposite of that. It holds itself at arm’s length. It’s a Christianity that no longer assumes that it has pride of place in the American cultural fabric, that it will be a better faith when they’re back to viewing themselves as exiles in their own land.

What kind of reaction have you had since the book came out? Have you heard from Christians, especially Evangelicals, who find it challenging, convincing, or perhaps just presumptuous?

It’s such a wide range. Of course I hear from the people who are most receptive to the message, and I’m under no illusions that I’m going to reach a MAGA audience with this message. It’s just not happening. But there are many, many Christians who are unhappy with the direction of the church. Just yesterday, I spent over an hour interviewing a pastor in Florida of a small church who’s part of what’s called the Post-Evangelical Collective. These are the homeless evangelicals who now feel that they can no longer abide the MAGA-fied church, but don’t want to give up their identities. And they’re starting to create resources and a home for that.

I think Christians like the fact that an outsider has come in and said that “I was wrong and that we were wrong on the secular side. We did not pay attention. We did not understand. We took you for granted.” And that has to change.

Many of our readers — with notable exceptions, I am sure — are Jews who share your concern that politics and religion shouldn’t mix the way they do now. If they’re concerned about what’s happening in Christianity, what can they do?

We can be curious; we can be welcoming. It wouldn’t hurt us to go with a friend to a church service. Alluding to what I said earlier, I think that secular people have pushed too far in the direction of secularizing the public square. It is not necessary or wise, for example, to insist that every single mom-and-pop bakery in the country cater to every single same-sex marriage. We need to make more space for people of faith to do their own thing, where that can be done with accommodations that don’t leave anybody else deprived of their rights.

But we Jews can’t fix this. Christians made this mess, and Christians have to fix it at the end of the day.

Keep Jewish Stories in Focus.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.

is editor at large of the New York Jewish Week and managing editor for Ideas for the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of JTA or its parent company, 70 Faces Media.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·