ARTICLE AD BOX

Joachim A. Lang’s groundbreaking approach merges two cinematic genres –Holocaust films and depictions of Nazi Germany – previously kept separate.

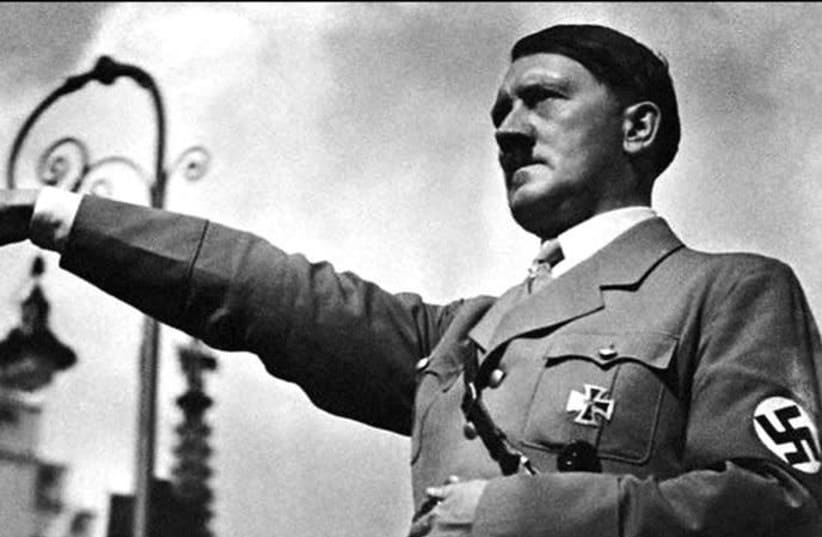

By YAEL BEN MOSHE JANUARY 26, 2025 02:34 El Führer alemán Adolfo Hitler haciendo el saludo nazi

(photo credit: Wikimedia Commons)

El Führer alemán Adolfo Hitler haciendo el saludo nazi

(photo credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Nearly 700 films featuring Hitler have been made since the end of World War II, yet few have offered new insights into this dark chapter of history or sparked meaningful public discourse. Most, like Downfall (2004) and Valkyrie (2008), were made for entertainment, but they inadvertently contributed to the mythologizing of Nazism and re-heroized Hitler.

Against this backdrop, Joachim A. Lang’s Goebbels and the Führer stands out as the first serious Hitler film in at least two decades.

Written and directed by Lang and screened in Jerusalem on January 1 at the Jewish Film Festival, the film traces Hitler and his propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels from the eve of Kristallnacht in 1938 to their deaths in Berlin in 1945. It exposes the mechanisms of disinformation and propaganda that fueled Nazism while drawing uncomfortable parallels to the modern age of fake news and media manipulation.

As such, Goebbels and the Führer is more than a historical film – it’s a critical exploration of propaganda’s enduring power. It deserves a global audience, not only for its fresh portrayal of Hitler and the Holocaust but also for its urgent relevance to contemporary media dynamics.

Filmed over 24 days in Slovakia with a modest budget due to resistance in Germany to confront Hitler on-screen, Lang turned challenges into creative freedom. The unconventional production enabled Lang to avoid the clichés of earlier Hitler films. The result is remarkable: a cast that understood the film’s significance, delivering performances devoid of glorification or unintended sympathy.

Unlike previous portrayals, Lang’s Hitler is neither a mythical figure nor a caricature of rage. Gone are the moments that evoked unintended empathy, as in Downfall, where Hitler’s relationship with his secretary elicited a measure of sympathy. Instead, Lang presents a Hitler defined by deep-seated antisemitism, racism, megalomania, and manipulativeness. This portrayal strips away the myths, showing Hitler as a man whose monstrous ideology drove his actions.

Lang’s groundbreaking approach

Lang’s groundbreaking approach merges two cinematic genres –Holocaust films and depictions of Nazi Germany – previously kept separate. By integrating authentic Holocaust footage into the narrative, Lang achieves something unprecedented. The footage is not merely illustrative but carefully contextualized, linked directly to the actions of Hitler and Goebbels.

This restores the dignity of the victims, who are no longer faceless figures but integral to the story. The film’s meticulous attention to historical accuracy transforms archival footage into a poignant narrative element, offering viewers a deeper understanding of the Holocaust’s atrocities.

A unique feature of the film is its inclusion of testimony from seven Holocaust survivors, including Margot Friedländer, who, at 102, graced the cover of Vogue Germany in 2024. These survivors act as moral counterpoints to Hitler and Goebbels, serving as the true heroes of the film.

Friedländer stresses the importance of recognizing the humanity behind Nazi crimes: “Human beings did it. Because they do recognize people as people. What happened can happen again so quickly.” Her warning underscores the film’s relevance in an era rife with manipulation and demagoguery.

Stay updated with the latest news!

Subscribe to The Jerusalem Post Newsletter

Charlotte Knobloch, another survivor featured in the film and former vice president of the World Jewish Congress, attended the premiere in Munich under police escort due to rising antisemitic threats.

She believes the film should have been made decades ago, before the resurgence of right-wing extremism and disinformation. “The film brings with it a new and challenging perspective for the viewer,” Knobloch observed. It compels audiences to reflect on their own responses to “political arsonists.”

Lang also draws on the unsettling insight of German novelist Thomas Mann, who, in his essay “Brother Hitler,” argued that Hitler’s impulses are disturbingly familiar, rooted in emotions we recognize in ourselves. The film echoes Holocaust survivor Primo Levi’s chilling reminder: “It happened... and therefore it can happen again. That is the core of what we have to say.”

As historical consultant Thomas Weber explains, the film’s urgency lies in its timeliness: “As the world has forgotten how Goebbels and Hitler wielded demagoguery, disinformation, and manipulation as weapons to devastating effect, the world no longer understands how to defend democracy and free societies, at a time at which we stand once more at the crossroads. This is why we made the film.”

By dismantling the myths around Hitler and confronting the viewer with uncomfortable truths, Goebbels and the Führer forces us to reckon with history – and ourselves. Its stark warning is clear: The mechanisms that enabled Nazism are not relics of the past but dangers we must confront today.

The writer is a lecturer on terrorism and communications and a researcher at the European Forum at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG), she is working on a project on the appropriation of historical footage, and conducts archaeological research on historical footage and photos from the Nazi era. She is the author of Hitler Konstruieren (Leipziger Universitätsverlag), on the depiction of Hitler in German and American films between 1945 and 2009, for which she studied between 200 and 300 Hitler films.

1 day ago

16

1 day ago

16

English (US) ·

English (US) ·