Three weeks after the Oct. 7, 2023, Hamas attack in Israel, a Jewish professor at Cornell University named Eric Cheyfitz offered a “teach-in” titled “Gaza, Settler Colonialism, and the Global War Against Indigenous People.”

Just before the teach-in, the school’s Jewish provost called him and asked if he wanted extra security.

Like other scholars of settler colonialism, Cheyfitz has long viewed Israel since its founding as a colonizer of indigenous Palestinian land, an argument that has gained increasing prominence in pro-Palestinian activism and that supporters of Israel reject. Now, Cheyfitz is turning that teach-in into a full-on course titled “Gaza, Indigeneity, Resistance,” which he’ll teach next term.

And that same provost, who has since become Cornell’s interim president, is opposed to the idea.

“I share your concerns and am extremely disappointed with the [school] curriculum committee’s decision to offer the course and the course’s apparent lack of openness and objectivity,” Michael Kotlikoff, the interim president, wrote on Thursday to another Jewish member of the faculty, Menachem Rosensaft, who had complained about Cheyfitz’s course.

The apparent shift in Kotlikoff’s thinking comes after a year in which administrators have been inundated with legal and political pressure — including calls from donors, activists and students — to protect Jewish and Israeli students. After the Hamas attacks, the start of the Gaza war and the intense university protests around the issue, administrators have felt pressure to be more assertive in monitoring the campus environment around Israel.

The classroom itself is shaping up as the next front in these clashes, particularly after the election. At Columbia University, prominent Palestinian-American professor Joseph Massad — who has faced scrutiny for appearing to paint Hamas in a positive light and calling images of the attack “awesome” — has also attracted criticism for a course he’s offering on the history of Zionism and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

“Individuals like Cheyfitz and others are going to try to use the curricula as the next line of delegitimizing Israel and using the curriculum in their courses for political purposes,” said Rosensaft, an adjunct professor in Cornell’s law school and former general counsel of the World Jewish Congress. “To a certain extent they hide and have coverage under academic freedom. So it’s up to the university and up to individuals like Mike Kotlikoff to make clear to students that they do not consider these courses to be academically legitimate.”

Kotlikoff ascended to the presidency after Cornell’s previous Jewish president stepped down in May, citing the campus climate around the Israel-Hamas war in Gaza. In the email to Rosensaft, which was viewed by the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, he elaborated on his objections.

“Cornell courses should provoke thought and present multiple viewpoints, rather than transmit pre-formed views of a complex conflict, and I personally find the course description to represent a radical, factually inaccurate, and biased view of the formation of the State of Israel and the ongoing conflict,” Kotlikoff wrote.

Kotlikoff added that, while concerns about infringing on academic freedom prevented him from intervening against the course, he was working with faculty focused on Israel and the Middle East to offer different kinds of courses so that “students interested in the history of the Middle East and Zionism will find more substantive and objective offerings.” The school intends to share Kotlikoff’s thoughts about the course with senior administrators as outside criticism of the course has mounted, according to Rosensaft.

In an interview, Cheyfitz said he objected to the very idea of the interim president weighing in on the details of a course curriculum.

“I’m actually kind of surprised,” Cheyfitz said when told about his president’s objections to the course. “I don’t think upper administrators should comment on faculty courses.”

During the teach-in, Cheyfitz recalled, Kotlikoff seemed only concerned with faculty safety: “He didn’t complain about the course itself,” he said.

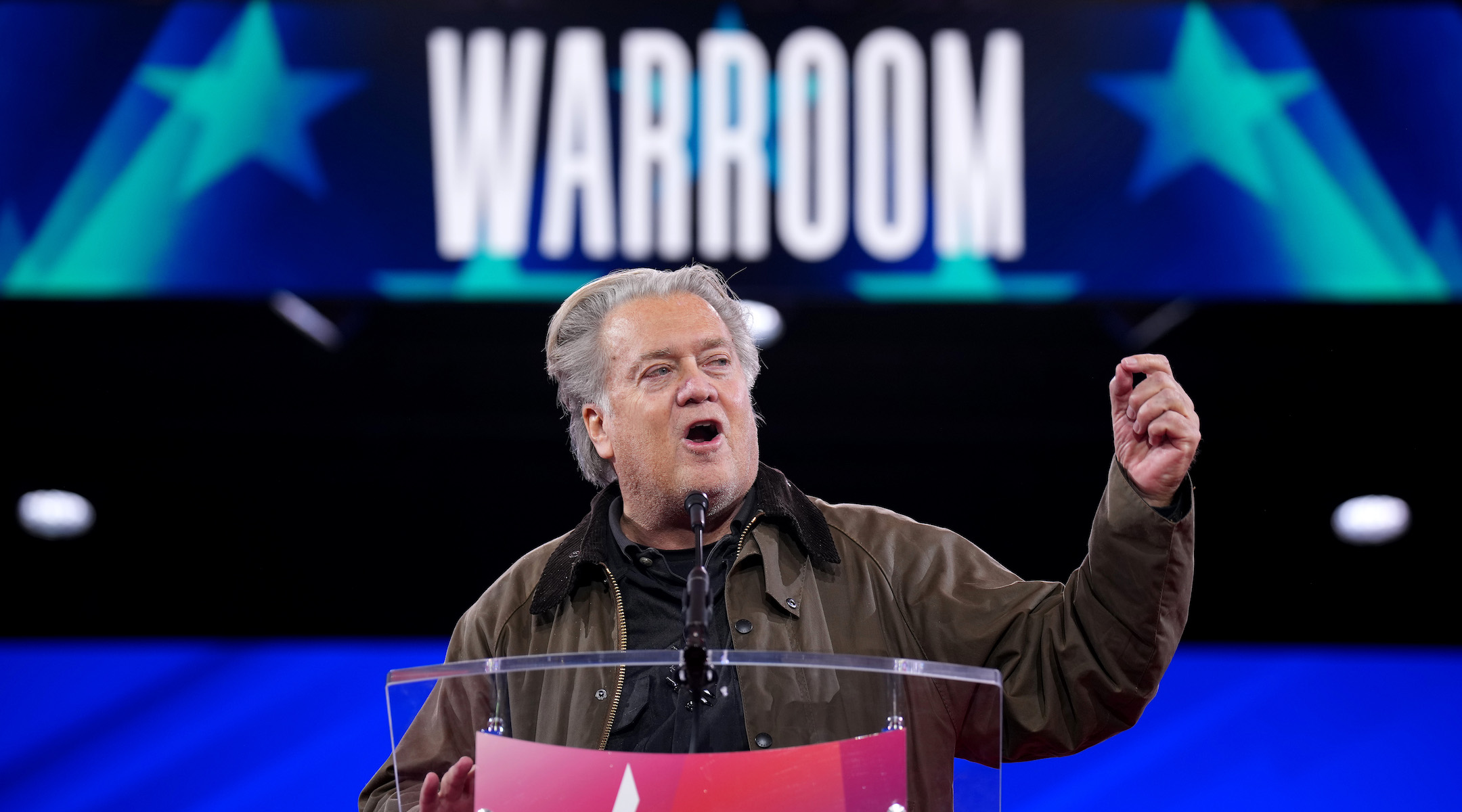

In his campaign, Donald Trump vowed to deport foreign pro-Palestinian student protesters, and to punish universities teaching what he deems to be “wokeness” and “jihadism.” (Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

This is not the first time classroom instruction has come under scrutiny from pro-Israel activists. The 2004 documentary “Columbia Unbecoming” featured testimony about anti-Israel biases in classroom discussions of the conflict at the New York Ivy, and also took aim at Massad. (Cheyfitz told JTA he was also interviewed for an upcoming documentary on campus free speech in the post-Oct. 7 landscape.)

But the battles over classroom instruction may be turbocharged in the two decades since, and especially with Donald Trump’s second presidential term approaching. In his campaign Trump vowed to deport foreign pro-Palestinian student protesters, and to punish universities teaching what he deems to be “wokeness” and “jihadism,” including by withholding federal endowments and national accreditation until they comply. He has also promised to “endow” new “non-political” higher education programs “with the billions we will collect by taxing the large endowments of private universities plagued by antisemitism.”

“In recent weeks, Americans have been horrified to see students and faculty at Harvard and other once-respected universities expressing support for the savages and jihadists who attacked Israel,” he said in a November 2023 campaign video announcing his sweeping proposal for an “American Academy.” He continued, “We spend more money on higher education than any other country, and yet they’re turning our students into communists and terrorists and sympathizers of many, many different dimensions.”

Trump has also vowed to shutter the Department of Education, a campaign promise that appears rooted in a range of longstanding conservative grievances against the agency and would affect Jewish students in multiple ways. This could include the potential curtailing of Title VI civil rights investigations against K-12 schools and colleges, which Jewish groups have increasingly relied on to litigate antisemitism claims over the past year.

Professors are facing other pressures as well. Over the past year, some schools have also taken steps to limit faculty involvement on matters that in the past were decided by shared governance.

In at least one sense, fallout from the Gaza war has already affected how universities are approaching the second Trump era. Following blowback over their post-Oct. 7 statements, many schools including Cornell set down “institutional neutrality” rules. Now, per those rules, relatively few college presidents have issued statements about the election, according to the Chronicle for Higher Education.

One notable exception is Michael Roth, the Jewish president of Wesleyan University, which did not adopt a neutrality policy. In a blog post Wednesday titled “Work to do after the election,” Roth vowed not to “voluntarily assist” with any requests to deport international students, faculty or staff. He added that his school’s commitment to academic freedom and diversity initiatives would remain unchanged, and inveighed against “official censorship or the soft despotism of pandering to commercial popularity.”

He added, “The classroom must remain a space for professors to share their professional expertise with students who could in turn explore ideas and methodologies without fear of imposed orthodoxies.”

Amanda Silberstein, a Jewish student at Cornell University, testifies before the U.S. House on the antisemitism she has experienced on campus as pro-Palestinian protesters demonstrate behind her, Washington, D.C., Nov. 8, 2023. (Screenshot via YouTube)

Cornell has been at the center of repeated firestorms over professors’ reactions to Oct. 7 and the Gaza war. The university previously placed Russell Rickford, another tenured professor, on leave after he said he was “exhilarated” by the Oct. 7 attacks, remarks for which he later apologized. Rickford is now back on campus, Cheyfitz said; the two co-lead a pro-Palestinian contingent of faculty. Over the weekend, Rickford spoke at a campus rally that merged anti-Trump and pro-Palestinian activism and was co-organized by Cornell Democrats, according to the student paper.

Last month, the student newspaper reported on a meeting between school administrators, Jewish parents and Cornell’s Hillel at which the school’s vice president said that pro-Palestinian faculty “will be scrutinized” in their classrooms and described new efforts to surveil and discipline students who engage in disruptive protests. At the meeting, the vice president also said the university’s free-speech principles would permit a representative from the Ku Klux Klan to speak on campus.

His remarks at the meeting drew blowback from students and faculty. He later sought to clarify his remarks in two different statements, writing, “To be clear, the KKK is abhorrent by any standard, and Cornell University would never invite a representative of the KKK to campus.”

In August, a former Cornell student was convicted in court after threatening to kill Jewish students there, and Jewish Cornell students testified before Congress lat November about the hostile environment they said they were facing on campus. Lawmakers have pressed the university to curb its student activism.

Now, Cheyfitz’s course is attracting a new wave of criticism. It will include an examination of the United Nations 1948 convention on genocide in the context of the post-Oct. 7 war in Gaza. It also includes readings by Ilan Pappé — an Israeli anti-Zionist academic who accused Israel of genocide three days after the Oct. 7 attack — and Palestinian-American historian Rashid Khalidi, who wrote a foundational text laying out the argument that Israel is a settler-colonial project.

The course description asks students to explore “the proposition that Indigenous people are involved historically in a global war against an ongoing colonialism” including in Gaza. Cheyfitz has written repeatedly that he considers Israel’s war against Hamas to be a genocide, that Israel is a “close fit” with Nazi Germany and, in 2014, that “Gaza has become an extermination camp, run by Jews.” Israel rejects the genocide charge.

Rep. Ritchie Torres, a New York Democrat, wrote on X that Cornell Professor Eric Cheyfitz “demonizes Israel and lionizes Hamas.” (Noam Galai/Getty Images)

Last week, New York Rep. Ritchie Torres called Cheyfitz a Hamas apologist on the social network X. Torres, one of the most outspoken pro-Israel Democrats in Congress, shared a graphic from the controversial anonymous watchdog group Canary Mission, which maintains public dossiers on pro-Palestinian activists.

“Eric Cheyfitz, who is a Cornell Professor, demonizes Israel and lionizes Hamas, treating good as evil and evil as good,” Torres wrote. “Poisonous professors like Cheyfitz are poisoning young minds at taxpayer expense.”

Then, echoing Trump’s proposal to defund universities, Torres added, “It is one thing for a free society to permit the poisoning. It is something else to subsidize it. Why do we?” Groups like the Amcha Initiative, which monitors campus antisemitism, have also said they want the government to withhold federal money from campuses where faculty support academic boycotts of Israel.

Through a university spokesperson, Kotlikoff, the interim president, declined to offer further comment on the course.

Rosensaft, who teaches a course on antisemitism through the law school, said he objected to Cheyfitz’s class because of the course description as well as its positioning within the school’s American Indian and Indigenous Studies Program, where Cheyfitz is a faculty member, rather than a Middle East studies program. The Indigenous Studies program has previously hosted pro-Palestinian events on campus, and the school’s pro-Palestinian encampment movement has demanded to expand the program into a department alongside a hypothetical Palestinian Studies program.

“People have Cheyfitz’s number,” Rosensaft said. “They understand where he’s coming from. And it becomes, to a certain extent, a caveat emptor warning for anybody wanting to take this course.”

Cheyfitz, for his part, told JTA he didn’t see a problem with the course or where it was being taught. He added that he has received no pushback from his colleagues over the course, but has heard from Jewish students who object to his reference to the term “genocide.”

“We clearly advocate for Indigenous rights around the world,” he said of his program, where he said he has taught classes on Palestinians before. “And we teach courses based around that advocacy.”

But though Rosensaft doesn’t want the class to be taught, and believes the federal government should work to curb campus antisemitism, he said he disagreed with Trump’s aggressive stance on policing universities.

“Simply put, Jewish students will not be safe on campuses where discrimination of any sort is directed at other groups or when intellectual and academic freedoms are jeopardized,” he said. “Campus protesters on all sides of the political spectrum should be held accountable for their actions, but not for legitimately expressing their views.”

Cheyfitz is not deterred by Trump’s stated plans for universities. Cornell’s own interest in limiting faculty activism, he said, was a greater issue.

“I can’t say I’m unconcerned about it,” he said. “But it’s not going to stop me from doing what I do.”

He added, “To me, scholarship is always a kind of form of activism.”

Support the Jewish Telegraphic Agency

Help ensure Jewish news remains accessible to all. Your donation to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency powers the trusted journalism that has connected Jewish communities worldwide for more than 100 years. With your help, JTA can continue to deliver vital news and insights. Donate today.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·