Sitting with about a dozen young Jewish professionals last week, 32-year-old Brooklynite Arielle Krule was passionately leading a discussion about two seemingly unrelated topics that are close to her heart: the Mishnah, the 2,000-year-old compendium of Jewish legal text, and Narcan, the life-saving medicine used to reverse opioid overdoses.

“We have merited to live in the time of a modern miracle, my friends,” said Krule, a licensed social worker who will be ordained as a rabbi by Yeshivat Maharat this coming June, referring to naloxone, the generic name for the overdose-reversing drug.

The group had assembled for a V’Ahavta Community Narcan Training, named for the Hebrew prayer that means “You shall love.” Leading training programs on how to use Narcan, while drawing upon the wisdom of Jewish tradition, is something Krule does regularly as founding director of Selah, an organization that she founded in 2023 as a “spiritual community for people in recovery and those who love them, grounded in Jewish tradition.”

“I want to start at home, build a safer community within the Jewish community, and have that trickle out,” she said.

Selah’s naloxone trainings focus on teaching Jews on how to use the drug to help anyone, Jewish or not, in need.

“Secretly, it’s my dream that Jewish people in New York would see it as a chiyuv, an obligation, that they carry Narcan,” she added. “Like that they know what to do when someone needs them, just [like] the way we celebrate Shabbat or Rosh Hashanah.”

As part of Selah’s mission, Krule — who was one of the New York Jewish Week’s 36 to Watch last year — aims to train 2,000 people this year, having trained more than 1,000 in 2024. Krule and Selah, which is affiliated with the Educational Alliance and has a team of three people, have brought their Narcan-training program to Hillels, shuls, rabbinical schools and Jewish centers across the New York area.

On an almost balmy January afternoon, she was in the Times Square office of Jewish Queer Youth, an organization that provides support and a comfortable space for LGBTQ Jews aged 13-23, particularly those from observant homes.

“If you are a person who likes tefillah, or prayer, there’s a blessing where we say ‘God, who revives the dead,’ which is a little weird, futuristic,” she told them. “However, this is as close as I feel like we get, that we can actually reverse an overdose.”

The number of drug-overdose deaths in the U.S. is five-fold what it was in 1999, having peaked with 108,000 deaths in 2021. Over 105,000 people across the United States died from a drug overdose in 2023, according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, and 3,046 of those deaths occurred in NYC. The most common substance involved being the highly potent opioid, fentanyl.

Statistics on opioid addiction among New York City’s Jewish community, in particular, can be more difficult to come by. A 2021 UJA-Federation of New York study on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on local Jews found that 10% of respondents indicated that they have a substance abuse problem, although the type of substance was not identified. Of those individuals, nearly 90% said they are “not seeking help.”

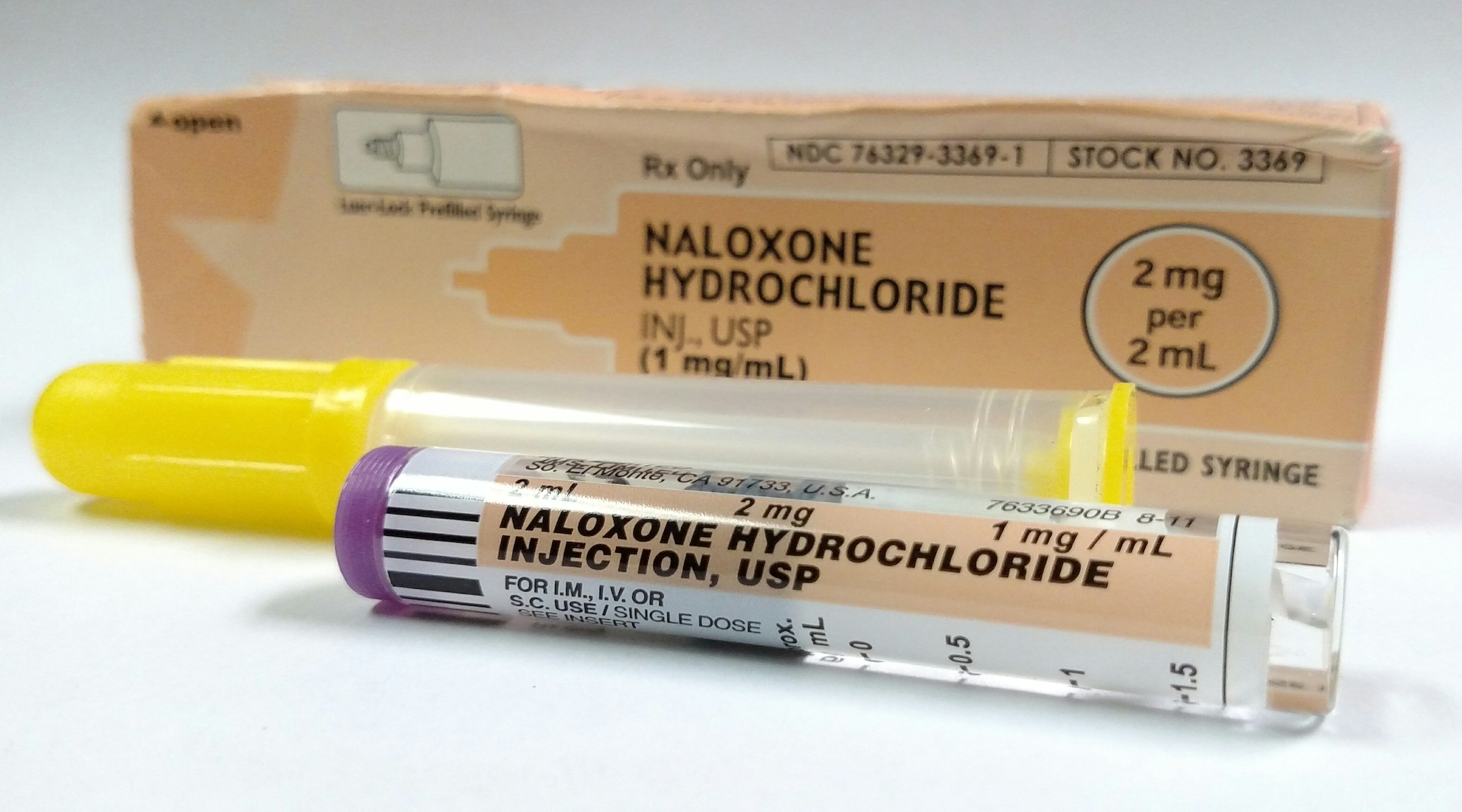

A naloxone kit includes applicators for administering a dose of the life-saving medication. (Wikimedia Commons)

Aside from UJA’s study, statistics about substance abuse generally do not specify religion, and many people in the community hide their abuse. A 2015 pilot study of Jews in Winnipeg, Manitoba, however, found that 41.2% knew someone currently struggling with an addiction, and that 23.5% reported having a family history of alcohol or drug abuse.

But there are signs that things are moving in a positive direction when it comes to opioid addiction: Since August 2022, naloxone has been available without a prescription at pharmacies across New York State to help combat the ongoing opioid epidemic. In 2023, overdose deaths in NYC decreased for the first time in four years. And nationally, the most recent numbers show a 21.7% decrease in overdose deaths in the 12-month period ending August 2024 versus the previous 12 months.

In her year-plus leading V’Ahavta Trainings, Krule said the most surprising thing she’s learned is how silent the Jewish community is on the subject of addiction. “I believed, anecdotally, that there was more addiction in the Jewish community than we talked about,” she said. “Constantly, every training, it is revealed to me more and more that we need to be talking about it and really building community about it.”

Krule and her Selah co-founders Benjamin Litchman and Jeremy Pool — all of whom are Jewish and have had experiences with addiction — held their first community Narcan trainings during Hanukkah 2023, visiting a different Jewish community each night across the five boroughs.

“We learned a lot about how, one: people don’t know this is an option for them to be safe and build a better community,” Krule told the New York Jewish Week. “And two: people need a space to talk about this.”

Krule describes what she calls “the shanda factor,” using the Yiddish word for shame or disgrace. “[Addiction is] not talked about in the Jewish community,” she said. “No one wants to be the person who brings it up, but whenever someone brings it up, there are many other people who say, ‘That also happened to me.’”

Last Tuesday’s training was the second time that Selah brought their training to JQY’s office.

“There’s definitely more overlap between [Selah’s] work and ours than we know about,” Maris Krauss, JQY’s expansion and college program manager, said. “There’s definitely a lot of addiction in the Jewish community, a lot of addiction in the LGBT community. And also our teens that maybe are coming from homes with people in recovery, or maybe they’re struggling, they don’t have the support.”

Krauss added, “There’s a lot of interwoven stuff going on, so just having them here is really cool.”

While this particular training was held during one of JQY’s “block parties” — a lunchtime gathering where Jewish professionals working in and around Times Aquare can connect with one another — Krauss said she hopes they’ll hold a training for JQY’s teenage clients.

That, Krauss said, would be “a way to make this accessible for younger people so they can be equipped to help a friend or family member or stranger.”

Plus, as Krule had told the group, teens often don’t call for help in overdose situations due to a fear of getting in trouble. These trainings, Krauss said, can help “make them aware that that’s not the case.”

Shlomo Rozenek, who works for NECHAMA, a Jewish nonprofit that provides disaster relief, came to the gathering because he was “intrigued” by the Narcan training. “I happen to know a lot of people who have substance use issues, so I figured it was a good idea for me to get trained,” he said.

Rozenek, 29, added that he “really liked” Krule’s incorporation of Jewish text, which wasn’t “strict to any denomination.” “I think that it serves as a bridge for people who don’t know about addiction issues that the Jewish community faces,” he said. “And [it’s] also a very practical way to hopefully help out if, God forbid, that’s needed.”

After running through the mechanics of administering Narcan — monitoring for slow breathing, testing for the person’s alertness with a shout and a sternal rub, spraying the Narcan up their nostril, calling 911 and turning the person onto their side while awaiting emergency services — Krule went clockwise around the circle, reaching into a large bag and handing everyone their own Narcan kit. (Over-the-counter kits are $38.)

It’s important thing to remember, she explained, was that it’s “rare for someone to die immediately” while overdosing: “There are seconds’, minutes’ time when we can respond.”

“Save one life,” Krule said to the group, quoting a famous passage from the Mishnah, “save an entire world.”

Jewish stories matter, and so does your support.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·